even as a shadow / even as a dream

At the start of 2020, I sat on an empty beach under the stars as the waves made blue whorls in the darkness, and I kissed the faces of those next to me around a campfire we had dug into the sand. We drank champagne from miniature bottles. When we finally went indoors, our skin was cold and imprinted with night; we stripped and stood in a sauna until the feeling came back to our fingers, washed out what smoke was in our hair. In the morning, I still smelled it on my pillowcase. That world which was this one, but not quite, feels so impossibly far that if I were to go to the beginning again, I would turn back. Don’t you know.

I can’t stop thinking about a line at the beginning of Anne Carson’s translation of Euripides’ Herakles. Herakles’ wife Megara and their children are to be killed unjustly by Lykos who has command of Thebes. Finishing his last labor in the underworld, Herakles is gone and his absence is felt as what is unfinished: “He went down there but has not come back.” Return predicates an assent towards order, in this case that his coming back will undo what occurred during his disappearance. What unspooled may be re-spun, the tragedy reversed. As she prepares her sacrifice for Hades, Megara cries out to Herakles as beloved, impossible return:

“Help us! Come back! Even as a shadow,

even as a dream.”

And moments later, he does. They rejoice. Perhaps they don’t know they are inside a tragedy, with its limbs towards disaster. Herakles’ return from the underworld precipitates his descent into madness by Hera’s demand, she who despises him for being Zeus’ son. Humility demands sacrifice, and what salvation Megara hoped Herakles’ would hearken is spilled into the same ending by different hands—in his madness, Herakles’ slays his wife and children, believing them different beings. Bound by law, Herakles is unable to even attend the funerals of his family, and instead leaves Thebes for Athens with Thesus, to whom he asks, “and yet you say I am made small by grief?”

It’s a sad play and as I read it on the train I kept returning to Megara’s cry, her invocation to Herakles to come back even in a form that was no form at all but haunting.

What shape makes an o like your mouth moments before a lover?

What is a portal, what is a hole?

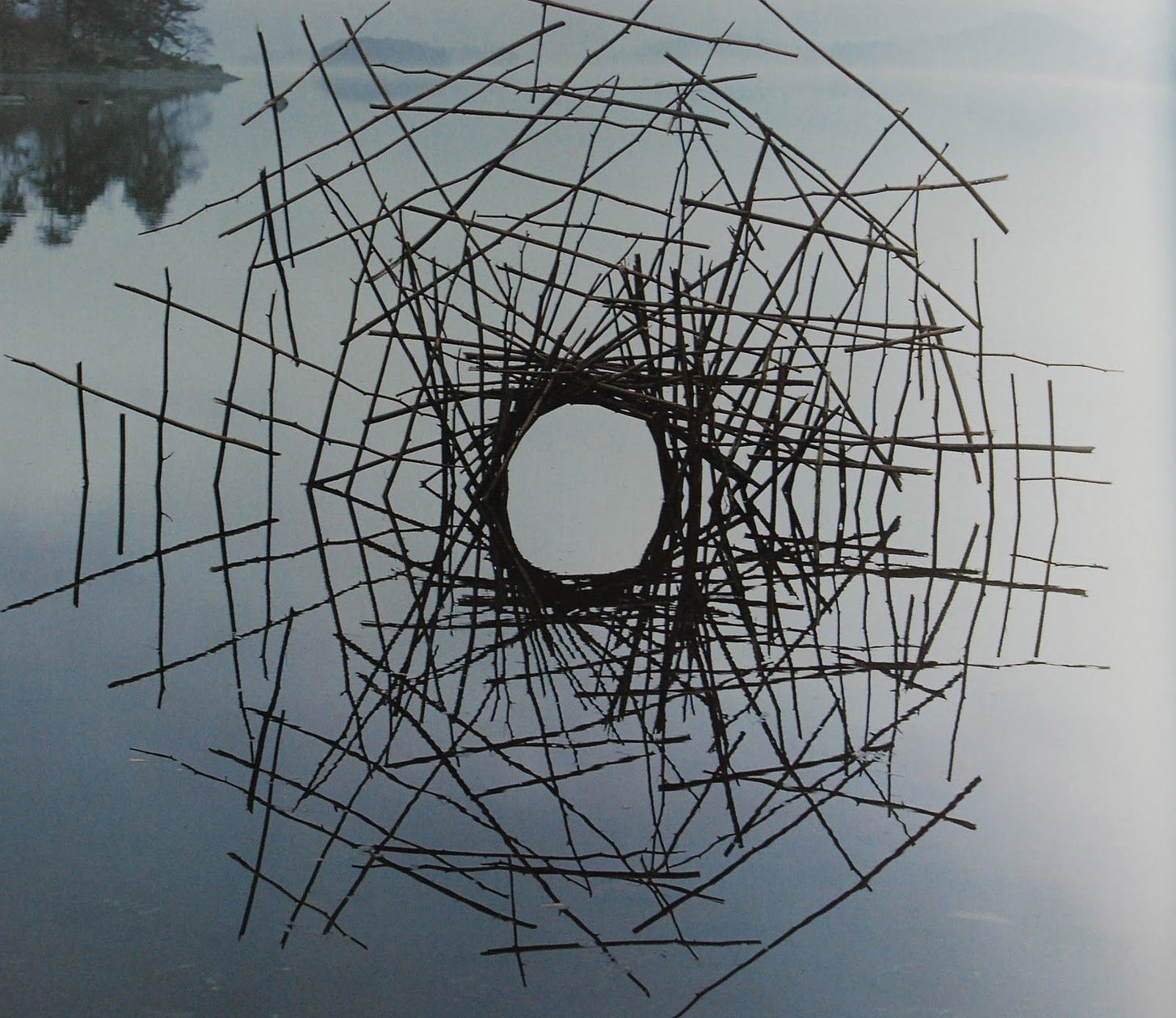

Screen 1998, Andy Goldsworthy

My nanny boys and I spent a morning looking through one of Andy Goldsworthy’s books. We paused on the images they liked (fanned plates of ice, ribboned leaves, a stone balancing atop a hill). I leafed through the photos again during one of their zoom classes and returned to this sculpture. I had traced the line of the water with my finger to show the boys where the lake split into its own reflection, and still, if I squint it seems possible that what inversions my eyes take for doubling are just a wreath of sticks rupturing place.

At the very center, the water is one tone and set against the interwoven bracken of the twigs, it appears less of a window and more of a hole. I want to crawl through the emptiness, disappear. It reminds me of of how as a child I wished to escape into the doorways C.S. Lewis opened in his Narnia chronicles, doorways flush to the meadows where you could not glance your hand if you stuck it through. The make-believe games I played when I was young always lingered at the edges of our world and another—a dimension only I could see, a portal like a layer of wind atop every surface. I fantasized about particles, waves. I made up physics to account for moving from one plane to the next.

I still have not outgrown this tendency towards thin spaces nor my affinity for ghosts. To come back as shadow: only the edges of a self brushed watery like a bruise; a particular square of twilight under a sheet; what hovers as frisson between our body and the ground. To come back as dream: here I maintain our slippery hands still touch; you saw a way to survive and were full of joy; the nature of a spiral as cyclical but not same.

To come back — that there is both path and place for return.

My mother mailed two boxes of childhood things to me in December and I spent a half hour on the floor rummaging through the contents: my basketball jersey from second grade; early journals with world maps and character sketches; baby photos; copies of my birth certificate; a box of childhood ornaments (the star from kindergarten, a green porcelain drum, my attempts at painted snowmen); the pink baby cap I came home from the hospital in; letters, birthday cards, post-it notes with no discernible beginning; old models for figure drawing; half a paint stand; folders for weddings I had photographed, each labeled and sorted with their respective intake forms and contracts; my power, or its shape.

My power was a small glass jar filled with colored sand, once layered and now one muddied spackle of grains. I carried it everywhere as a child, insistent that I could not leave the house without the vial. In church, I would hold it up during the passing of the peace, proclaim to everyone that all was well, I had my power.

Now it sits on my altar shelf next to a carved wooden fish from a dinner with an old lover. “Is there never any escaping the junkshop of the self?” Ali Smith asks. Every rupture unearths some forgotten beginning. The countless hours spent considering physicality and its potentiality for reincarnation in philosophy classes in college, suddenly meaningless at the edge of a loved one’s death. Can one come back from an experience that rends past and present like a wound? Or is return predicated less on resuming a remembered body and instead stepping through the perforation made by its rupture?

If you look closely, the edges shimmer. If you look closely, the bracken spiral towards a threshold. No more answers, only questions turned gateways returned to us.